Mvua!

Our short rainy season – kusi – has certainly come in with a bang! It always contrasts with the balmy climatic clemency of June to October. But the sheer persistence of this season’s day-long downpours, and relentlessness of wet day after wet day, is usually reserved for the wettest week of the long masika rains in May.

November rains usually bless us with more gentle and refreshing short, sharp showers. Rain to bring relief to farmers, not floods and fears of lost harvest. This year’s deluge is something else.

At least farmers were alerted in good time to expect exceptional rains this season. There is only so much mitigation they can do of course: other than clear drains and sow rain-resilient crops in good time before the rains arrive.

Rains are usually a welcome blessing!

So why is it so exceptionally wet this year? And how were meteorologists able to predict this anomaly with such confidence?

The answer lies far away in the Eastern South Pacific, where warmer-than-usual sea surface temperatures have triggered a global climate phenomenon known as El Niño.

Trade winds usually blow the warm water west, driving ocean currents. But this year, weak trade winds left the warm water in the eastern Pacific, blocking the usual upwelling of cooling currents, to trigger a cascade of climatic consequences around the world by disrupting oceanic currents and trade winds.

Climate scientists thus anticipate extreme weather world-wide during the coming months: some regions can expect prolonged droughts during El Niño years, while other regions – including ours – experience extreme rainfall.

At times like this, our existence as an integral part of nature’s system, not set apart from it, is brought home to us.

Healthy ecological systems help us survive. But where we have cut trees from slopes, soils erode and mudslides wipe out farms, crops, roads and even homes. Rivers burst their banks, flooding floodplains – along with any settlements ill-advisedly constructed there.

“Tunza mazingira yakutunze!” Swahili proverb

In Zanzibar’s coral-rag forests, natural caves in the limestone bedrock swallow up great volumes of rainwater that slowly filters into the groundwater – serving as natural flood control – except where they have been bulldozed by construction projects and filled with rubble and taka taka. Now, newly-built homes in areas that previously did not flood are underwater too.

Zanzibar’s unique and precious natural flood control is in peril

Consider how much water even a single flower stem can absorb from a vase of water. Multiply that effect to the size of a mighty tree, and imagine how much floodwater a flourishing forest can drink up! And then, reflect upon what happens to that floodwater if all the trees are cut. It is sobering, isn’t it?

Tree-grown produce like coconuts will weather the storms, but soft vegetable harvests will likely suffer

On farms, the coconuts, limes and mangos will weather the storm, and even the cassava. But soft vegetables are being battered into the earth. Even seaweed farmers are not spared – the turbid freshwater flowing off the land can smother the light- and salt-dependent algal harvest.

Polyculturalists will be the most resilient farmers – whether new permaculture graduates or traditional subsistence home-gardeners, cultivating a diversity of crops means at least some should make it. The more complex and natural the vegetation cultivated, the more water the land will take up.

But conventional modern monoculture practitioners may lose a whole crop, thus a season’s income, to an extreme weather event like this.

In urban areas, the roads will be miserable for a while. But the real concern must be for public health. Mosquitoes thrive in stagnant flooded pools, and if toilet pits flood into wells, cholera outbreaks are a possibility. Taka taka blocking drainage ditches makes flooding worse: inadequate waste collection leads to flooded streets and backed-up sewers, and the rubbish ends up on our seafood platters and beautiful beaches.

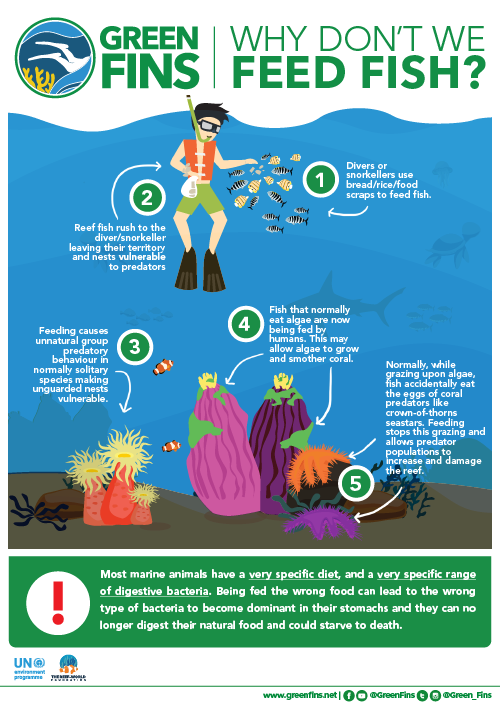

Other ecological impacts are likely. Our ocean heats up in El Nino years, which triggers stressed corals to spit out the algae that usually live inside and feed them. The corals become white (or bleached) without the coloured algae they depend on. Unless the water cools soon to allow the algae to come back, our corals that are already stressed by overfishing will die, along with many reef-dwelling animals. This is bad news for everyone whose livelihoods depends on marine ecosystems, from fisheries to snorkel guides.

Stormy Stone Town

© Suzanne Degeling

All of us should make sure our household rubbish is properly collected, and not later dumped near drains, mangroves or beaches. Take the opportunity to express gratitude to the people who clean our communities – a grim task in this weather – and support them by joining in community and beach cleaning efforts.

On that note, a shout out to Kawa Environment Club and Vikokotoni Environment Society for their tireless daily cleaning efforts, to PPIZ and Msonge Organic Family Farm for helping farmers implement more climate-resilient agroforestry practices, to Mohamed Bajubeir for his awareness-raising videography and to Labda Kesho for keeping our spirits up in spite of the inclement conditions.

Lastly, thank you to you for reading my rainy story and supporting the educational mission of this website if you can (links below).

Stay dry, and see you in the wilderness.

Meet the team

Nell Hamilton M.Sc.

Nell is a coastal ecologist, ecological gardener & nature storyteller, and the founder of www.zanzibarwildlife.com.

Nell is available for teaching, training and workshops, and freelance & consultancy through www.OurGreen.Company. She also writes at Ecologue.

Her Shorebird Poster ID Guide and Lunar Calendars are in stock at Green Market in Hurumzi (near Emerson Spice) and other local stockists.

Be the change you want to see in the world

If you are in a position to support our work to share knowledge and understanding of Zanzibar wildlife through this site, we are developing a content sponsorship programme. Meanwhile, if you find this interesting or helpful, donations at www.ko-fi.com/NellH help us keep telling Zanzibar wildlife stories.

You can also help us keep records up to date by logging your wildlife sightings on iNaturalist, and you can connect with us and join the conversation on Facebook and Instagram.

To read this site in Kiswahili click here.